Words by Nicola Bacon, Above image: South Acton new public space (photo credit: Social Life)

16 Jun 2025

Social design: the key to building 1.5 million new homes

In the latest Design Council Digest, Nicola Bacon, Design Council expert and Founding Director of research agency Social Life discusses the importance of social design in taking forward current plans for housebuilding.

Nicola Bacon, Social Life

The UK government has committed to building 1.5 million new homes in the lifetime of this Parliament. This is much needed. Latest government statistics show that 126,000 people are living in temporary accommodation including 164,000 children[1]. 1.33 million people are on council housing waiting lists[2] but only 260,000 households were given a new social housing tenancy last year[3].

Past failure of social design

But experience shows that high ambitions to build new homes, however urgently they are needed, do not necessarily translate into thriving communities that support wellbeing over time. It can be too easy to overlook the social needs of communities in the drive for delivery. This failure of social design can have stark consequences for both new and longstanding residents. In response, Social Life has developed a framework for social sustainability to help improve the planning, design and management of new places.

What do we know?

The record of new housebuilding at scale in the UK has some great successes, including utopian communities like New Lanark and Saltaire, garden cities and some of the post-war new towns. However other places have failed, becoming unpopular and unloved. At worst new housing development can damage wellbeing – in the early days of Cambourne near Cambridge problems emerged about isolation and mental ill health. This resonates with the very early experience of British new towns and the phenomenon that became known as the “New Town Blues”, associated with social isolation after moving to a new place where there aren’t enough facilities to socialise, find support and build new social networks.

We know a lot about how to boost the social dimensions of places. Design can bring people from different backgrounds together, it can boost local identity and belonging, it can encourage footfall and make places feel safe and create opportunities for neighbours stop and chat. Design can make places work for children, families and older people, it can provide space for good social infrastructure, along with green spaces for playing, hanging out, exercising, growing and planting. So how is it that it is so difficult to prioritise the social dimensions of design in policy and practice?

Very few people would say that new housing should de-prioritise the needs of communities, but there is often a sense that this is “too difficult” in practice. That taking on board the intangibles of human experience is tricky and mystifying, and far less certain than designing the physicality of buildings or landscape. Our experience demonstrates that this is incorrect, that we can design, plan and manage places to boost social value and improve the quality of everyday life.

Our social sustainability framework

Social Life first published “Design for Social Sustainability” in 2012. We have deployed the framework over the last 12 years in the UK and internationally – in London alone we have applied it in 20 places. This is a tried and tested framework that supports fresh thinking and helps agencies work together to imagine the social design of places in new ways. We reviewed and updated the framework last year to reflect a greater sensitivity to spatial justice, to the values of green space, nature and the outdoor, to the urgency of the climate crisis and to the importance of community resilience – starkly illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

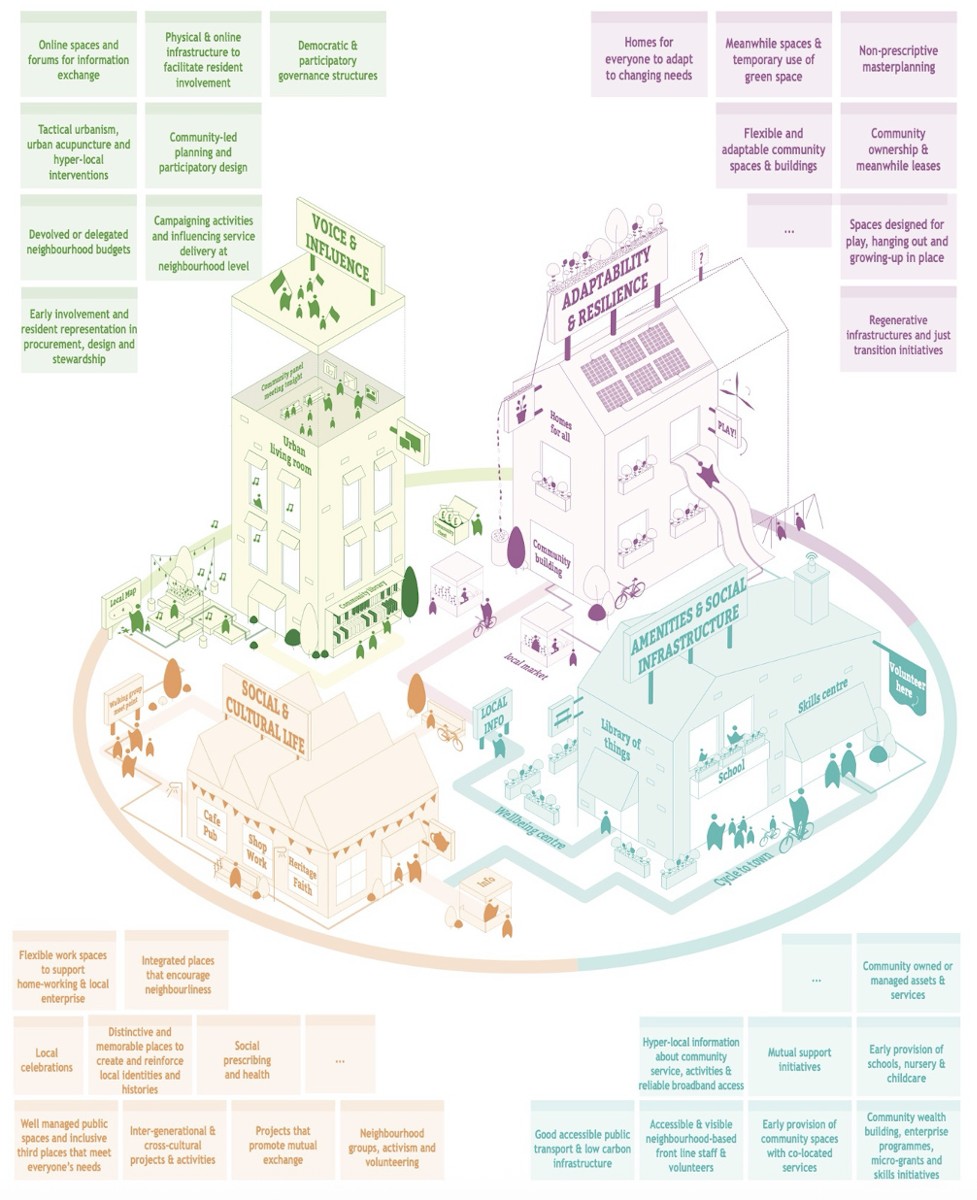

Our framework focuses on four elements that are essential to build new communities that will be successful and sustainable in the long term: Amenities & Social infrastructure; Social & Cultural life; Voice & Influence; and Adaptability & Resilience. All four elements are needed in every place, however social success and sustainability cannot be prescribed and described in the same way as standards for green building or job creation. Flexibility is needed to reflect local circumstances and the particular nature of every community and its residents.

Building blocks for social sustainability: these illustrate the practical steps that can be taken to boost each dimension

How is this useful?

Our work has fresh relevance as housing policy refocuses on housebuilding at scale. Our framework provides a tool to improve the social value of new developments, to support innovation, and to measure the social impact of built environment changes. It is a thinking tool as well as a tool for action.

Social sustainability continues to be understated in mainstream sustainability debates and practice. Priority has tended to be given to economic and environmental sustainability. Despite its relevance to debates about social value, the Sustainable Development Goals and, in England, to the National Planning Policy Framework, and to the Design Council’s “Design for Planet” mission, there are few practical resources that directly address how to create places that are socially sustainable.

In the UK we now have a government committed to building new towns and urban extensions and making existing urban areas more dense. Their overall aim is to tackle our entrenched housing crisis. In this drive towards rapid house building, we must take care and consider what type of places and communities we are creating. New housing must be sustainable and support wellbeing and quality, creating homes and communities; it must deliver social value to places and communities as well as meeting housing targets. If it does not the cost will fall on their residents, and Managing the long-term costs and consequences of poor social design and social failure is an issue of public value and political accountability.

Clapham Park Estate Fun Day 2024 Credit: Social Life

What is needed?

Getting this right is critical to the Design for Planet mission as well as the long term success of government ambitions for 1.5 million new homes. We need to make stronger and deeply practical links between design that promotes environmental sustainability and social design. An understanding of social design needs to become much more firmly embedded in the work of built environment professionals, from planners and surveyors to architects and landscape designers. Social design is key to our concepts of regenerative design - design that promotes long term co-existence of people and planet.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/...

- https://www.social-life.co/publication/Social-Sustainability - Design for Social Sustainability (2012)

- https://www.social-life.co/publication/designing_for_social_sustainability - Designing Social Sustainability (2012). This refreshes and updates the 2012 publication.

- https://www.social-life.co/publication/embedding_social_value_in_the_design_process - Embedding social value in the design process (2023)

- https://www.social-life.co/publication/social_impacts_regeneration_S_Acton_assessment_3 - Measuring the social impacts of regeneration in South Acton: third social sustainability assessment (2021)

- https://www.socialsustainabilityglos.org - Social sustainability toolkit Gloucestershire. An online resource developed by the Barnwood Trust and Social Life.